A car’s brake lights suddenly flash in our face.

We don’t stop to evaluate. We react instantly to this latest signal.

A star player commits too many errors in a row. The coach doesn’t rely on the player’s many successful games. He reacts to these signals and makes a substitution.

A sales rep hears a new objection and pivots mid-call to save the deal.

Bottom line: We’re built to pay attention to what just happened.

This recency attribute has helped us survive, adapt, and respond when things move fast.

Yet it can also be a trap.

The Recency Bias Trap

Any sports fan will dwell on the last few plays of a tight game, while ignoring everything that contributed before.

We celebrate the rep who closed the deal that pushed us over the quarterly target, while giving less credit to the steady deals that got us close.

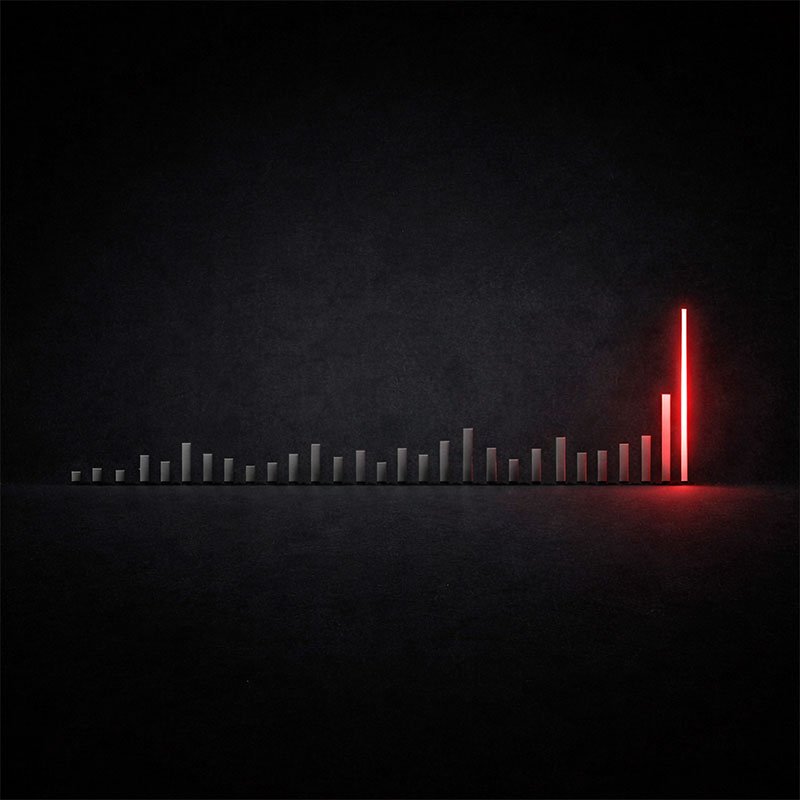

We look at last week’s sales numbers and declare sweeping changes, ignoring many months of solid progress.

The last thing feels the loudest.

But loud doesn’t always mean most important.

Left on autopilot, our human programming takes over.

Recency Bias Studied

Our tendency to overweight the most recent events has been studied for decades.

In the 1960s, researchers ran a simple experiment: read people a list of words, then ask them to recall. The last words were remembered best. That’s the recency effect. Short-term memory keeps what just happened at the front of our mind.

Modern research goes further. A 2018 study showed that when judging what they were looking at, people leaned on what they had just seen. The previous image biased how they perceived the current one, even though the two weren’t connected.

In 2024, neuroscience studies confirmed the bias isn’t just habit. It’s wired into how memory and perception work.

And another study that same year found resisting recency requires extra effort from the cognitive-control regions of the brain.

And we see it beyond the lab.

Investors often overreact to the latest market move. Surveys show most admit recency bias drives them to chase “hot stocks” or flee after a sudden drop in price.

In summary, these studies:

- Show our brain doesn’t process each moment in isolation.

- Instead, perception blends with what just happened, almost like a “mental afterimage.”

- This bias occurs even when the past stimulus is irrelevant to the current judgment.

- Effort is required to overcome this bias.

Recency Bias in All of Us

We aren’t alone in our recency bias. Everyone has it. That means we have to account for it in how we communicate and design experiences.

This can work for us or against us.

On the positive side, we can use recency bias with intention. Marketers know the beginning and the end of a message are what stick the most. That means the way we frame an opening matter, and the way we close matters even more. Whether it’s a presentation, a pitch, or an email, put the most important point where it will be remembered.

On the negative side, a single bad moment at the end can overshadow an otherwise great customer experience. Experts in customer-journey design suggest reinforcing earlier positives and managing endings carefully, so one stumble doesn’t erase the goodwill built along the way.

Recency bias shows up everywhere: in how people remember our words, and in how they judge their experiences.

We can’t turn it off, but we can decide how to use it.

That’s where a few simple rules help.

Using Our Recency Bias

Recency bias isn’t a flaw. It’s a feature.

Follow these three rules to embrace the benefits and avoid the traps:

1. Acknowledge it.

Our brains are wired to overweight the most recent event. By naming it, we see more clearly how we and others are processing what just happened.

2. Check the trend.

Before making a decision, ask: does this recent signal fit the long-term pattern, or is it an outlier? One customer complaint may reveal a real issue or just be noise.

3. Anchor to the foundation.

Let recent signals inform adjustments, but always test them against your strategy, values, and long-term goals. The foundation keeps you steady.

Putting the Rules to Work

Imagine a leadership team reviewing last quarter’s results. Revenue dipped.

Acknowledge it: They notice their instinct to fixate on the dip. They should and it’s natural.

Check the trend: Looking back three years, revenue has grown steadily. One bad quarter doesn’t erase that.

Anchor to the foundation: Their strategy is to expand into new markets. The slowdown came from one region, not the strategy itself. Instead of overreacting, they refine execution and stay the course.

Key Takeaway

Recency bias is human.

It has kept us sharp when quick reactions matter.

But not all decisions require a split-second response.

If we treat every signal like a crisis, we risk chasing noise instead of seeing the whole pattern.

That’s where the bias can hurt us.

Yet, the answer isn’t to fight it. It’s to use it.

Acknowledge it. Check the trend. Anchor to the foundation.

And if you only remember this line of my post… well, that’s recency bias at work.