We all love being right.

We build our plans, test our ideas, and celebrate when the results confirm what we already believed.

While that feeling is satisfying, it’s also what can make us blind.

The Wason Trap

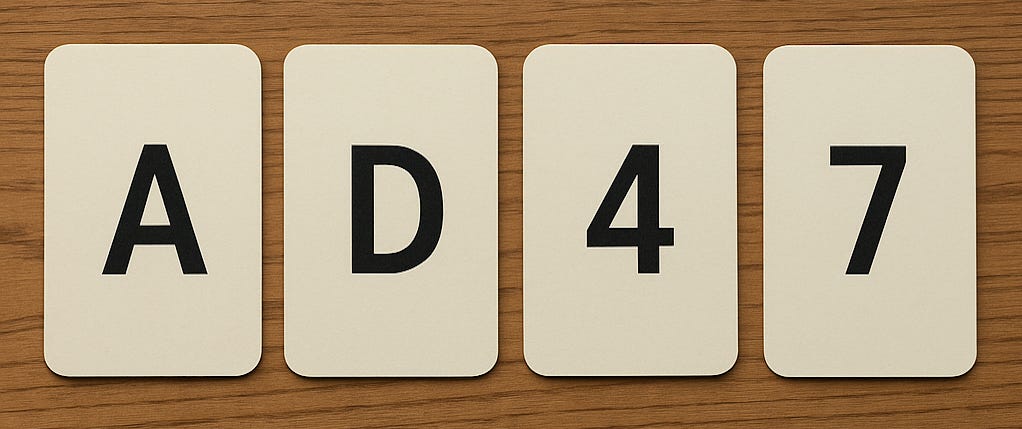

In the 1960s, psychologist Peter Wason ran a now-famous experiment. He showed participants four cards: A, D, 4, 7. Each had a letter on one side and a number on the other.

The rule was simple:

If there’s a vowel on one side, there’s an even number on the other.

The task:

Which cards would you flip to test the rule?

Most people picked A and 4. They wanted to see more evidence that the rule worked.

But the right answer is A and 7. Because the only way to test the rule is to look for what would disprove it.

We don’t naturally do that.

We look for confirmation, not contradiction.

The Science of Disproof

Science thrives not on what’s proven, but on what hasn’t yet been disproven.

History gives us a powerful example.

In mid-19th-century London, cholera was ravaging neighborhoods.

Doctors were convinced they knew why: bad air (or “miasma”).

It made perfect sense. The poorest districts smelled awful. Sewers overflowed.

When city crews cleaned up the filth, cases dropped…sometimes.

To everyone, that was proof enough.

They saw exactly what they expected and stopped looking deeper.

Yet, this confirmation bias turned out to be deadly.

Then came John Snow (no, not Jon Snow; it had nothing to do with winter).

Snow doubted the air theory. Too many deaths didn’t fit the pattern.

So, he worked to disprove the prevailing air theory.

He mapped every death during the 1854 Soho outbreak. The pattern centered on one place: the Broad Street water pump.

Families who drank from that pump got sick.

Neighbors who drank beer instead stayed healthy. (A tempting, albeit biased, slogan for a brewer.)

When officials removed the pump handle, cholera cases plummeted while the air hadn’t changed at all.

The air theory looked like “fact”. Confirmation bias told us so.

Yet, Snow asked:

“What if the air has nothing to do with it?”

That question separated correlation from cause and saved lives.

Confirmation in Action

While our own confirmation bias may not be life or death, they certainly can shape how we grow our businesses.

We launch new features and track early users.

But are we testing to prove we were right or to see if we were wrong?

We run forecasts, get one good result, and assume our strategy works.

We see an uptick in sales and call it validation.

But what if it was luck? As I wrote in Mistaking Luck for Judgment, a good outcome doesn’t always mean we made a good decision.

What if our success came from timing, or a single client, or a market tailwind we didn’t control?

That’s how we fall into the same trap Wason exposed:

We test to confirm, not to learn.

Test to Learn

As I wrote in How the Best Stay Ahead showed, the smartest teams challenge what’s working before it breaks.

Let’s use a simple example and follow a process.

Assume that our sales increased by 25% in Product X this past quarter.

Everyone believes that it was due to our new pricing. As a result, we want to apply this new pricing to our other products too. Everyone is excited!

But was the 25% increase similar to the air theory John Snow disproved?

Let’s test it by following three steps:

1. State the Thesis

We need to know what we are assuming; what is our underlying thesis.

In this example, we have a thesis:

“Product X sales increased by 25% because we introduced new pricing.”

Yet, what we know is simple correlation:

- We introduced new pricing AND

- Product X sales increased by 25%.

If we simply wish to confirm our thesis, we can stop here. I’m confident we can find many instances where we changed our pricing and got a sale. No different than choosing A-4 in the Wason test or relying on the “air theory”.

If we are going to rely on this thesis to make a business decision (e.g., roll out new pricing to other products), it would be best to challenge it.

2. Challenge with Alternative Theories

We need to identify what other factors could have contributed to the increase.

Identify what else changed. For example, possible changes last quarter:

- New feature shipped

- Fresh messaging or campaign

- End-of-year urgency

- Channel push

- One whale customer

Business is always changing; and I realize it may be difficult to isolate exact changes, but the idea is to consider other theories.

Using your alternative theories, run analysis to challenge them. Think like a scientist and work to disprove.

What remains is a solid thesis.

3. Test

For either the original thesis, or a revised one, my advice is simple: Test it.

I’ve been known to have a thesis or two that would “kill it” only to have them fail wildly. My enthusiasm was blinding.

I would have been smarter to test them first.

Whether it’s new messaging, a new call-to-action, new pricing, etc. testing is the only objective way to obtain good data.

Reflection

The goal isn’t to doubt everything. It’s to earn conviction.

So this week, ask yourself:

Where in your business are you testing to be right, instead of testing to be wrong?

At Forge & Fathom, we help companies do exactly that: stress-test their go-to-market engines and separate correlation from cause.

Want to test your engine right now? Check out our Fathom360 Quickcheck. It only takes 5 minutes.