Beating the odds doesn’t mean you made a good decision – and a good decision isn’t always a lucky one.

We often judge our choices by how things turn out.

But what if that’s a trap?

In poker — and in business — the best players win not by chasing luck, but by making smart, repeatable decisions.

Can you tell if your last “good” call was really good, or just lucky…

Let’s test this idea:

- Can you recall the last bad decision that resulted in a good outcome?

- Or the last good decision that led to a bad outcome?

It’s hard to do.

We’re conditioned to believe that a decision is defined by how things turn out.

But what if that’s exactly where we go wrong?

What if there is a world where:

A good decision can have a bad outcome; and

A bad decision can have a good outcome.

That may be uncomfortable to sit with. We want the world to be cleaner than that.

But the world is rarely clean.

Introducing: Resulting

In her bestselling book,Thinking in Bets, former World Series of Poker champion Annie Duke introduced me to the concept of resulting:

Resulting is our tendency to equate the quality of a decision with the quality of its outcome.

We all do it. I do it.

But that bias is dangerous, because it leads us to praise bad decisions when they work and dismiss good decisions when they don’t.

And that’s a problem. Because in business, the quality of your decisions is what determines whether your success is repeatable — or just lucky.

Let me show you what I mean.

Two Decisions, Two Outcomes

Situation #1

I had a conversation with a potential client about their sales challenges. I casually suggested pursuing a new market segment. No research — just a high-level idea. The CEO, desperate for any solution, jumped on the idea and mobilized the team. They saw immediate and positive results. As it turned out, that market segment was underserved, not only by my client but by the market overall.

Question: Did the CEO make a good or bad decision?

Situation #2

Another CEO took a more methodical path. They re-examined their Ideal Customer Profile, mapped their buyer’s journey, and tested new messaging with both customers and prospects. The CEO and team were excited and launched with confidence. But sales stayed flat. No traction.

Question: Did the CEO make a good or bad decision?

Good or Bad?

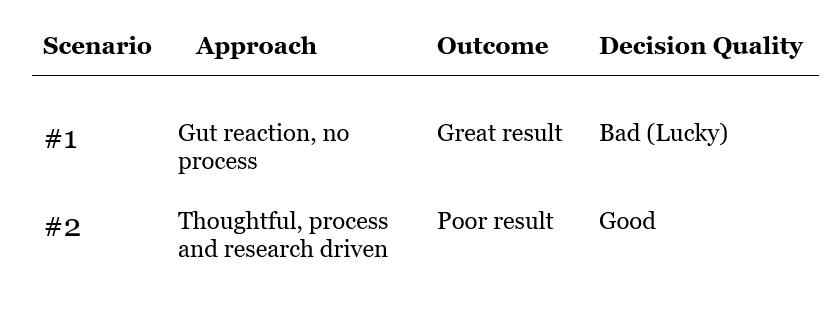

Let’s look beyond the outcomes and focus on the approach taken. Additionally, I’ll provide a view on whether the decision was “good” or “bad”.

Are we still sure that outcomes tell the whole story?

Most people would praise CEO #1 for their instincts and criticize CEO #2 for overthinking.

Flip the outcomes, and people flip their judgment.

That’s resulting in action.

So What Makes a Decision Good?

Simple: Repeatability.

If you made a similar decision ten times, using the same process, would it produce the desired result more often than not?

That’s the heart of evaluating decisions well.

In poker, the best players win consistently not because they’re lucky, but because they make high-quality decisions based on known odds. They understand the difference between process and variance:

- Process is how you make the decision — the logic, information, and structure behind it.

- Variance is the randomness in outcomes — the part you can’t control.

A good process increases your odds, but it doesn’t guarantee the result.

And a bad outcome doesn’t mean the process was flawed—it may just reflect variance.

We can’t control the outcome, but we can certainly control the process.

While business doesn’t have the same precision as poker, business does have patterns, probabilities, and risks that can be evaluated as part of our decision-making process. The more we refine our decision-making — evaluating tradeoffs, testing assumptions — the more repeatable our decisions (and successes) become.

Now, I’m not promoting a conservative approach. I recognize there will be times when we need to go with our instinct or make high risk decisions. That’s fine.

But we need to not delude ourselves into thinking that the result will define the quality of the decision.

In poker, you might go all-in with a terrible hand and still win.

But that doesn’t mean it was a good decision – or one you should repeat.

Key Takeaway (TL; DR)

Good outcomes don’t always mean good decisions. And bad outcomes don’t always mean bad ones.

We fall into the trap of resulting — evaluating decisions by how things turned out, not how they were made.

But leadership isn’t about gambling for results. It’s about building a process you trust — one you’d stand by even when the outcome doesn’t go your way.

A good decision is repeatable. It’s made with intention, informed by insight, and aligned with your goals.

The real question isn’t “Did it work?”

It’s “Would I make that same decision again, knowing what I knew at the time?”

A good decision process should be repeated; bad decisions shouldn’t. Thus, knowing whether a decision was good or bad is vital.

While good luck never hurt, I wouldn’t bet on it.